The Dye Is Cast

After another swig of the medicine, a shot of local Drum whiskey, Dave Scard, the long-time camp guide at Joyo’s Surf Camp at G-Land, gritted his teeth and placed a fibreglass cast over his back bent leg. A few days before the Australian had broken his tibia pulling into a large tube on the Javanese reef.

He had two options; return to the closest hospital in Bali or fly back home to Queensland and have it dealt with there. Scard however had taken a scarcely believable third. Using the fibreglass matting and resin he used to fix the many Al Bryne six-channelled surfboards he snapped each year at the break, he’d made a fibreglass cast for his leg and set the fracture himself (many years later Scard would release the shaper Byrne’s ashes whilst in a tube at G-Land, I kid you not). He didn’t want it set straight, as most orthopaedic doctors would prescribe, but instead fixed it in the tube stance that would allow him to surf G-Land.

Now this was my first evening at the wave located on the very eastern tip of Java. I was initially horrified. Scard’s devotion was, clearly, insane. After spending a week there though, his actions seemed entirely rational. It is a wave that inspires devotion. A surfing outpost that, thankfully, hasn’t, or won’t change. Surfers have spent decades trying to decode the many moods of this incredible mile of reef. Some get close. Most just keep coming back trying the pick the lock.

The World’s First Surf Camp

The wave has inspired devotion ever since the first surfers to set eyes on the wave. That was Americans Bob Laverty and Bill Boyum. Traveling in a plane over the very eastern tip of Java to Bali in 1972 they looked out the window and saw a massive coral reef located deep in Javanese jungle that had endless waves wrapping down its huge expanse. Once in Bali, they set about finding it. Armed with 70 CC Suzuki motorbikes, tattered navy maps and not quite enough food, they found the wave after three long days. It was as perfect as they dreamed it would be.

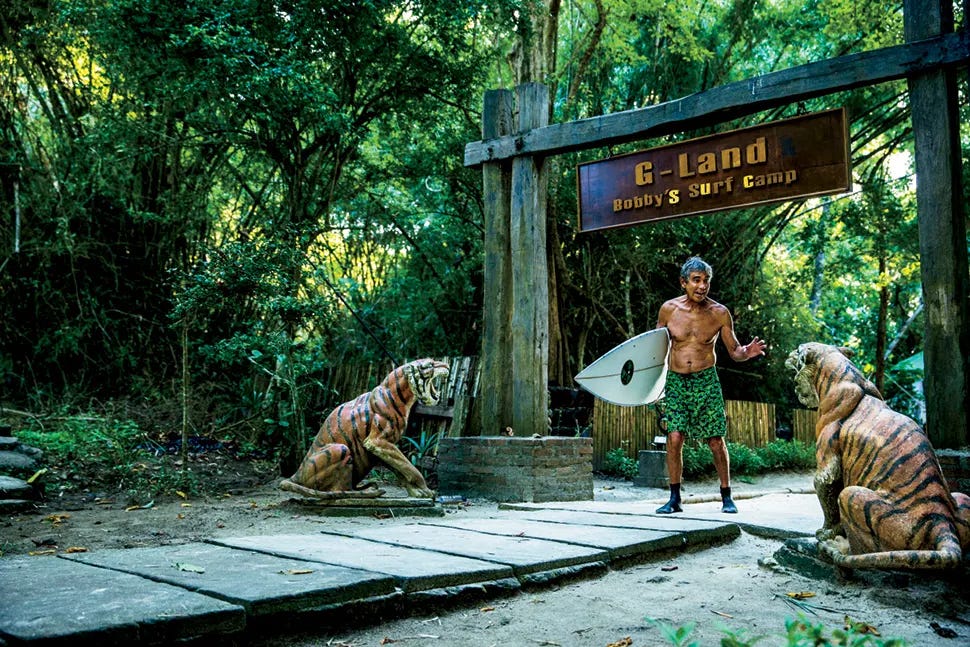

Knowing the wave was one of the best in the world Boyum and his brother Mike established some basic accommodation. The primitive set up was the prototype for the world’s first surf camp. By the late 1970s, Balinese entrepreneur Bobby Radiassa took charge of organizing guests and the camp, still called Bobby’s, operations. And the beauty of the Grajagan is that while many things have changed since those early days, most haven’t.

Sure, the Suzukis have been replaced by a two-hour speed boat ride from Kuta Beach. And rather than mosquito nets hoisted on high wooden sleeping platforms (the local tigers were a concern) the accommodation is now comfortably ground feline proof and air-conditioned.

Morning Sickness and Truman Capote

But the wave that inspired Laverty’s devotion and Scard’s self-doctoring remains as alluring as ever. The remote setting also inspires camaraderie. On that first day, I sat down at the communal breakfast bar next to a camp guest. He asked for the salt, I told him to fuck off, and we both laughed. We both had books by Truman Capote; mine a battered copy of In Cold Blood, his Breakfast at Tiffany’s. That started a conversation which started a friendship that has endured to this day. Following a breakfast of banana pancakes, mango smoothie and a mug of mud-thick Javanese coffee (a menu choice I’ve stuck with for two decades), the empty line-up had me scrambling for my equipment for my first surf.

Matt, a G-Land veteran, however, advised me to slow down. The offshore breeze he explained kicks in almost every day around ten am. Before then, the waves are lumpy and imperfect. Well, for G-Land standards anyway. That has the effect of making for lazy mornings, yet laced with the adrenalin of anticipation.

After a few more chapters of Capote and a stretch, I felt the warm air start to blow off the jungle towards the ocean. The lumps were removed and the imperfections were erased. The ten-minute walk through the jungle to the top of the reef was, and remains, a sensory overload. Every 50 yards or so a gap in the dense foliage reveals another section of the Grajagan reef and perfect lefthanders roping down at breakneck speed.

Getting Sectioned

At the tip of the reef you enter the water and make your way through a series of semi-channels to the outer wave known as Kongs. This receives the most swell and breaks even on the smallest swells. It is also forgiving and provides G-Land’s best section for intermediate surfers.

Next down is a section called Fan Palms. A smaller takeoff zone than Kongs, and slightly more uniform, it still hoovers up the smaller swells up the top of the reef, but doesn’t provide the world-class waves G-Land is known for. That starts down the reef at Money Trees, the most consistent and most photogenic part of the reef. I’d stared at a poster on my wall as kid showing a lone surfer leaning against a palm tree watching the perfect green walls of this section. Such was the imprint on my malleable grommet’s mind I doubted whether the reality could ever match the mind surfing I’d done.

That was allayed as soon as I stroked into a low tide wave that collapsed over the shallow coral slab at the tip of the reef. An adrenalin-fuelled high-line barrel was followed by a 300-yard green wall of water that didn’t have a single drop of water out of place. If it was perfect from land it felt dreamlike riding the wave.

Speedies: The Holy Grail

After three hours, and with the tide pushing up, the final section of the reef, Speedies sparked into life. It is the jewel of all G-land’s many sections (long-term visitors will carve the reef up into as many as eight named parts of the reef). My first wave started off with a relatively easy takeoff at the aptly named Launching Pads, before spinning down a 300-yard racetrack. It offered deep, throaty emerald barrel, intense adrenalin and euphoria. Later I would also receive a violent underwater assault, the outcome depending on how successfully surfere can deal the extremely shallow section of the reef.

It was for this section of the wave where I saw the fibreglass-casted Scard screaming through the six-foot green tube. His normal smooth tube style was a little tweaked, but the effectiveness couldn’t be questioned. He may have been causing long-lasting damage (four months and hundreds of tubes later he would have the leg broken and reset by a surgeon) but his stoke was undeniable.

Later that day after two long and memorable surfs, I sat with Scard, my new friend Matt and my fellow camp guests drinking some cold beers and watching the sunset backlight the perfect waves. There were whales breaching out to sea, a family of monkeys bathing in the rock pools near shore and a mongoose sifting through the sand for crabs. Our evening was soundtracked by the roar of the ocean, the murmur of the jungle and the laughter of surfers knowing they were in the right place at the right time.

For around 50 years surfers have repeated and tweaked the lazy-morning, two-surfs-a-day, beers-at-sunset, Indonesian-rice-dish-then-bed, routine. It’s why the world’s first surf camp still has a claim to be its best.